Advanced usage

ASN.1 and SNMP

What is ASN.1?

Note

This is only my view on ASN.1, explained as simply as possible. For more theoretical or academic views, I’m sure you’ll find better on the Internet.

ASN.1 is a notation whose goal is to specify formats for data exchange. It is independent of the way data is encoded. Data encoding is specified in Encoding Rules.

The most used encoding rules are BER (Basic Encoding Rules) and DER (Distinguished Encoding Rules). Both look the same, but the latter is specified to guarantee uniqueness of encoding. This property is quite interesting when speaking about cryptography, hashes, and signatures.

ASN.1 provides basic objects: integers, many kinds of strings, floats, booleans, containers, etc. They are grouped in the so-called Universal class. A given protocol can provide other objects which will be grouped in the Context class. For example, SNMP defines PDU_GET or PDU_SET objects. There are also the Application and Private classes.

Each of these objects is given a tag that will be used by the encoding rules. Tags from 1 are used for Universal class. 1 is boolean, 2 is an integer, 3 is a bit string, 6 is an OID, 48 is for a sequence. Tags from the Context class begin at 0xa0. When encountering an object tagged by 0xa0, we’ll need to know the context to be able to decode it. For example, in SNMP context, 0xa0 is a PDU_GET object, while in X509 context, it is a container for the certificate version.

Other objects are created by assembling all those basic brick objects. The composition is done using sequences and arrays (sets) of previously defined or existing objects. The final object (an X509 certificate, a SNMP packet) is a tree whose non-leaf nodes are sequences and sets objects (or derived context objects), and whose leaf nodes are integers, strings, OID, etc.

Scapy and ASN.1

Scapy provides a way to easily encode or decode ASN.1 and also program those encoders/decoders. It is quite laxer than what an ASN.1 parser should be, and it kind of ignores constraints. It won’t replace neither an ASN.1 parser nor an ASN.1 compiler. Actually, it has been written to be able to encode and decode broken ASN.1. It can handle corrupted encoded strings and can also create those.

ASN.1 engine

Note: many of the classes definitions presented here use metaclasses. If you don’t look precisely at the source code and you only rely on my captures, you may think they sometimes exhibit a kind of magic behavior.

``

Scapy ASN.1 engine provides classes to link objects and their tags. They inherit from the ASN1_Class. The first one is ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL, which provide tags for most Universal objects. Each new context (SNMP, X509) will inherit from it and add its own objects.

class ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL(ASN1_Class):

name = "UNIVERSAL"

# [...]

BOOLEAN = 1

INTEGER = 2

BIT_STRING = 3

# [...]

class ASN1_Class_SNMP(ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL):

name="SNMP"

PDU_GET = 0xa0

PDU_NEXT = 0xa1

PDU_RESPONSE = 0xa2

class ASN1_Class_X509(ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL):

name="X509"

CONT0 = 0xa0

CONT1 = 0xa1

# [...]

All ASN.1 objects are represented by simple Python instances that act as nutshells for the raw values. The simple logic is handled by ASN1_Object whose they inherit from. Hence they are quite simple:

class ASN1_INTEGER(ASN1_Object):

tag = ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL.INTEGER

class ASN1_STRING(ASN1_Object):

tag = ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL.STRING

class ASN1_BIT_STRING(ASN1_STRING):

tag = ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL.BIT_STRING

These instances can be assembled to create an ASN.1 tree:

>>> x=ASN1_SEQUENCE([ASN1_INTEGER(7),ASN1_STRING("egg"),ASN1_SEQUENCE([ASN1_BOOLEAN(False)])])

>>> x

<ASN1_SEQUENCE[[<ASN1_INTEGER[7]>, <ASN1_STRING['egg']>, <ASN1_SEQUENCE[[<ASN1_BOOLEAN[False]>]]>]]>

>>> x.show()

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_INTEGER[7]>

<ASN1_STRING['egg']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_BOOLEAN[False]>

Encoding engines

As with the standard, ASN.1 and encoding are independent. We have just seen how to create a compounded ASN.1 object. To encode or decode it, we need to choose an encoding rule. Scapy provides only BER for the moment (actually, it may be DER. DER looks like BER except only minimal encoding is authorised which may well be what I did). I call this an ASN.1 codec.

Encoding and decoding are done using class methods provided by the codec. For example the BERcodec_INTEGER class provides a .enc() and a .dec() class methods that can convert between an encoded string and a value of their type. They all inherit from BERcodec_Object which is able to decode objects from any type:

>>> BERcodec_INTEGER.enc(7)

'\x02\x01\x07'

>>> BERcodec_BIT_STRING.enc("egg")

'\x03\x03egg'

>>> BERcodec_STRING.enc("egg")

'\x04\x03egg'

>>> BERcodec_STRING.dec('\x04\x03egg')

(<ASN1_STRING['egg']>, '')

>>> BERcodec_STRING.dec('\x03\x03egg')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<console>", line 1, in ?

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2178, in do_dec

l,s,t = cls.check_type_check_len(s)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2076, in check_type_check_len

l,s3 = cls.check_type_get_len(s)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2069, in check_type_get_len

s2 = cls.check_type(s)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2065, in check_type

(cls.__name__, ord(s[0]), ord(s[0]),cls.tag), remaining=s)

BER_BadTag_Decoding_Error: BERcodec_STRING: Got tag [3/0x3] while expecting <ASN1Tag STRING[4]>

### Already decoded ###

None

### Remaining ###

'\x03\x03egg'

>>> BERcodec_Object.dec('\x03\x03egg')

(<ASN1_BIT_STRING['egg']>, '')

ASN.1 objects are encoded using their .enc() method. This method must be called with the codec we want to use. All codecs are referenced in the ASN1_Codecs object. raw() can also be used. In this case, the default codec (conf.ASN1_default_codec) will be used.

>>> x.enc(ASN1_Codecs.BER)

'0\r\x02\x01\x07\x04\x03egg0\x03\x01\x01\x00'

>>> raw(x)

'0\r\x02\x01\x07\x04\x03egg0\x03\x01\x01\x00'

>>> xx,remain = BERcodec_Object.dec(_)

>>> xx.show()

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_INTEGER[7L]>

<ASN1_STRING['egg']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_BOOLEAN[0L]>

>>> remain

''

By default, decoding is done using the Universal class, which means objects defined in the Context class will not be decoded. There is a good reason for that: the decoding depends on the context!

>>> cert="""

... MIIF5jCCA86gAwIBAgIBATANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQUFADCBgzELMAkGA1UEBhMC

... VVMxHTAbBgNVBAoTFEFPTCBUaW1lIFdhcm5lciBJbmMuMRwwGgYDVQQLExNB

... bWVyaWNhIE9ubGluZSBJbmMuMTcwNQYDVQQDEy5BT0wgVGltZSBXYXJuZXIg

... Um9vdCBDZXJ0aWZpY2F0aW9uIEF1dGhvcml0eSAyMB4XDTAyMDUyOTA2MDAw

... MFoXDTM3MDkyODIzNDMwMFowgYMxCzAJBgNVBAYTAlVTMR0wGwYDVQQKExRB

... T0wgVGltZSBXYXJuZXIgSW5jLjEcMBoGA1UECxMTQW1lcmljYSBPbmxpbmUg

... SW5jLjE3MDUGA1UEAxMuQU9MIFRpbWUgV2FybmVyIFJvb3QgQ2VydGlmaWNh

... dGlvbiBBdXRob3JpdHkgMjCCAiIwDQYJKoZIhvcNAQEBBQADggIPADCCAgoC

... ggIBALQ3WggWmRToVbEbJGv8x4vmh6mJ7ouZzU9AhqS2TcnZsdw8TQ2FTBVs

... RotSeJ/4I/1n9SQ6aF3Q92RhQVSji6UI0ilbm2BPJoPRYxJWSXakFsKlnUWs

... i4SVqBax7J/qJBrvuVdcmiQhLE0OcR+mrF1FdAOYxFSMFkpBd4aVdQxHAWZg

... /BXxD+r1FHjHDtdugRxev17nOirYlxcwfACtCJ0zr7iZYYCLqJV+FNwSbKTQ

... 2O9ASQI2+W6p1h2WVgSysy0WVoaP2SBXgM1nEG2wTPDaRrbqJS5Gr42whTg0

... ixQmgiusrpkLjhTXUr2eacOGAgvqdnUxCc4zGSGFQ+aJLZ8lN2fxI2rSAG2X

... +Z/nKcrdH9cG6rjJuQkhn8g/BsXS6RJGAE57COtCPStIbp1n3UsC5ETzkxml

... J85per5n0/xQpCyrw2u544BMzwVhSyvcG7mm0tCq9Stz+86QNZ8MUhy/XCFh

... EVsVS6kkUfykXPcXnbDS+gfpj1bkGoxoigTTfFrjnqKhynFbotSg5ymFXQNo

... Kk/SBtc9+cMDLz9l+WceR0DTYw/j1Y75hauXTLPXJuuWCpTehTacyH+BCQJJ

... Kg71ZDIMgtG6aoIbs0t0EfOMd9afv9w3pKdVBC/UMejTRrkDfNoSTllkt1Ex

... MVCgyhwn2RAurda9EGYrw7AiShJbAgMBAAGjYzBhMA8GA1UdEwEB/wQFMAMB

... Af8wHQYDVR0OBBYEFE9pbQN+nZ8HGEO8txBO1b+pxCAoMB8GA1UdIwQYMBaA

... FE9pbQN+nZ8HGEO8txBO1b+pxCAoMA4GA1UdDwEB/wQEAwIBhjANBgkqhkiG

... 9w0BAQUFAAOCAgEAO/Ouyuguh4X7ZVnnrREUpVe8WJ8kEle7+z802u6teio0

... cnAxa8cZmIDJgt43d15Ui47y6mdPyXSEkVYJ1eV6moG2gcKtNuTxVBFT8zRF

... ASbI5Rq8NEQh3q0l/HYWdyGQgJhXnU7q7C+qPBR7V8F+GBRn7iTGvboVsNIY

... vbdVgaxTwOjdaRITQrcCtQVBynlQboIOcXKTRuidDV29rs4prWPVVRaAMCf/

... drr3uNZK49m1+VLQTkCpx+XCMseqdiThawVQ68W/ClTluUI8JPu3B5wwn3la

... 5uBAUhX0/Kr0VvlEl4ftDmVyXr4m+02kLQgH3thcoNyBM5kYJRF3p+v9WAks

... mWsbivNSPxpNSGDxoPYzAlOL7SUJuA0t7Zdz7NeWH45gDtoQmy8YJPamTQr5

... O8t1wswvziRpyQoijlmn94IM19drNZxDAGrElWe6nEXLuA4399xOAU++CrYD

... 062KRffaJ00psUjf5BHklka9bAI+1lHIlRcBFanyqqryvy9lG2/QuRqT9Y41

... xICHPpQvZuTpqP9BnHAqTyo5GJUefvthATxRCC4oGKQWDzH9OmwjkyB24f0H

... hdFbP9IcczLd+rn4jM8Ch3qaluTtT4mNU0OrDhPAARW0eTjb/G49nlG2uBOL

... Z8/5fNkiHfZdxRwBL5joeiQYvITX+txyW/fBOmg=

... """.decode("base64")

>>> (dcert,remain) = BERcodec_Object.dec(cert)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<console>", line 1, in ?

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2094, in do_dec

return codec.dec(s,context,safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2218, in do_dec

o,s = BERcodec_Object.dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2094, in do_dec

return codec.dec(s,context,safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2218, in do_dec

o,s = BERcodec_Object.dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2099, in dec

return cls.do_dec(s, context, safe)

File "/usr/bin/scapy", line 2092, in do_dec

raise BER_Decoding_Error("Unknown prefix [%02x] for [%r]" % (p,t), remaining=s)

BER_Decoding_Error: Unknown prefix [a0] for ['\xa0\x03\x02\x01\x02\x02\x01\x010\r\x06\t*\x86H...']

### Already decoded ###

[[]]

### Remaining ###

'\xa0\x03\x02\x01\x02\x02\x01\x010\r\x06\t*\x86H\x86\xf7\r\x01\x01\x05\x05\x000\x81\x831\x0b0\t\x06\x03U\x04\x06\x13\x02US1\x1d0\x1b\x06\x03U\x04\n\x13\x14AOL Time Warner Inc.1\x1c0\x1a\x06\x03U\x04\x0b\x13\x13America Online Inc.1705\x06\x03U\x04\x03\x13.AOL Time Warner Root Certification Authority 20\x1e\x17\r020529060000Z\x17\r370928234300Z0\x81\x831\x0b0\t\x06\x03U\x04\x06\x13\x02US1\x1d0\x1b\x06\x03U\x04\n\x13\x14AOL Time Warner Inc.1\x1c0\x1a\x06\x03U\x04\x0b\x13\x13America Online Inc.1705\x06\x03U\x04\x03\x13.AOL Time Warner Root Certification Authority 20\x82\x02"0\r\x06\t*\x86H\x86\xf7\r\x01\x01\x01\x05\x00\x03\x82\x02\x0f\x000\x82\x02\n\x02\x82\x02\x01\x00\xb47Z\x08\x16\x99\x14\xe8U\xb1\x1b$k\xfc\xc7\x8b\xe6\x87\xa9\x89\xee\x8b\x99\xcdO@\x86\xa4\xb6M\xc9\xd9\xb1\xdc<M\r\x85L\x15lF\x8bRx\x9f\xf8#\xfdg\xf5$:h]\xd0\xf7daAT\xa3\x8b\xa5\x08\xd2)[\x9b`O&\x83\xd1c\x12VIv\xa4\x16\xc2\xa5\x9dE\xac\x8b\x84\x95\xa8\x16\xb1\xec\x9f\xea$\x1a\xef\xb9W\\\x9a$!,M\x0eq\x1f\xa6\xac]Et\x03\x98\xc4T\x8c\x16JAw\x86\x95u\x0cG\x01f`\xfc\x15\xf1\x0f\xea\xf5\x14x\xc7\x0e\xd7n\x81\x1c^\xbf^\xe7:*\xd8\x97\x170|\x00\xad\x08\x9d3\xaf\xb8\x99a\x80\x8b\xa8\x95~\x14\xdc\x12l\xa4\xd0\xd8\xef@I\x026\xf9n\xa9\xd6\x1d\x96V\x04\xb2\xb3-\x16V\x86\x8f\xd9 W\x80\xcdg\x10m\xb0L\xf0\xdaF\xb6\xea%.F\xaf\x8d\xb0\x8584\x8b\x14&\x82+\xac\xae\x99\x0b\x8e\x14\xd7R\xbd\x9ei\xc3\x86\x02\x0b\xeavu1\t\xce3\x19!\x85C\xe6\x89-\x9f%7g\xf1#j\xd2\x00m\x97\xf9\x9f\xe7)\xca\xdd\x1f\xd7\x06\xea\xb8\xc9\xb9\t!\x9f\xc8?\x06\xc5\xd2\xe9\x12F\x00N{\x08\xebB=+Hn\x9dg\xddK\x02\xe4D\xf3\x93\x19\xa5\'\xceiz\xbeg\xd3\xfcP\xa4,\xab\xc3k\xb9\xe3\x80L\xcf\x05aK+\xdc\x1b\xb9\xa6\xd2\xd0\xaa\xf5+s\xfb\xce\x905\x9f\x0cR\x1c\xbf\\!a\x11[\x15K\xa9$Q\xfc\xa4\\\xf7\x17\x9d\xb0\xd2\xfa\x07\xe9\x8fV\xe4\x1a\x8ch\x8a\x04\xd3|Z\xe3\x9e\xa2\xa1\xcaq[\xa2\xd4\xa0\xe7)\x85]\x03h*O\xd2\x06\xd7=\xf9\xc3\x03/?e\xf9g\x1eG@\xd3c\x0f\xe3\xd5\x8e\xf9\x85\xab\x97L\xb3\xd7&\xeb\x96\n\x94\xde\x856\x9c\xc8\x7f\x81\t\x02I*\x0e\xf5d2\x0c\x82\xd1\xbaj\x82\x1b\xb3Kt\x11\xf3\x8cw\xd6\x9f\xbf\xdc7\xa4\xa7U\x04/\xd41\xe8\xd3F\xb9\x03|\xda\x12NYd\xb7Q11P\xa0\xca\x1c\'\xd9\x10.\xad\xd6\xbd\x10f+\xc3\xb0"J\x12[\x02\x03\x01\x00\x01\xa3c0a0\x0f\x06\x03U\x1d\x13\x01\x01\xff\x04\x050\x03\x01\x01\xff0\x1d\x06\x03U\x1d\x0e\x04\x16\x04\x14Oim\x03~\x9d\x9f\x07\x18C\xbc\xb7\x10N\xd5\xbf\xa9\xc4 (0\x1f\x06\x03U\x1d#\x04\x180\x16\x80\x14Oim\x03~\x9d\x9f\x07\x18C\xbc\xb7\x10N\xd5\xbf\xa9\xc4 (0\x0e\x06\x03U\x1d\x0f\x01\x01\xff\x04\x04\x03\x02\x01\x860\r\x06\t*\x86H\x86\xf7\r\x01\x01\x05\x05\x00\x03\x82\x02\x01\x00;\xf3\xae\xca\xe8.\x87\x85\xfbeY\xe7\xad\x11\x14\xa5W\xbcX\x9f$\x12W\xbb\xfb?4\xda\xee\xadz*4rp1k\xc7\x19\x98\x80\xc9\x82\xde7w^T\x8b\x8e\xf2\xeagO\xc9t\x84\x91V\t\xd5\xe5z\x9a\x81\xb6\x81\xc2\xad6\xe4\xf1T\x11S\xf34E\x01&\xc8\xe5\x1a\xbc4D!\xde\xad%\xfcv\x16w!\x90\x80\x98W\x9dN\xea\xec/\xaa<\x14{W\xc1~\x18\x14g\xee$\xc6\xbd\xba\x15\xb0\xd2\x18\xbd\xb7U\x81\xacS\xc0\xe8\xddi\x12\x13B\xb7\x02\xb5\x05A\xcayPn\x82\x0eqr\x93F\xe8\x9d\r]\xbd\xae\xce)\xadc\xd5U\x16\x800\'\xffv\xba\xf7\xb8\xd6J\xe3\xd9\xb5\xf9R\xd0N@\xa9\xc7\xe5\xc22\xc7\xaav$\xe1k\x05P\xeb\xc5\xbf\nT\xe5\xb9B<$\xfb\xb7\x07\x9c0\x9fyZ\xe6\xe0@R\x15\xf4\xfc\xaa\xf4V\xf9D\x97\x87\xed\x0eer^\xbe&\xfbM\xa4-\x08\x07\xde\xd8\\\xa0\xdc\x813\x99\x18%\x11w\xa7\xeb\xfdX\t,\x99k\x1b\x8a\xf3R?\x1aMH`\xf1\xa0\xf63\x02S\x8b\xed%\t\xb8\r-\xed\x97s\xec\xd7\x96\x1f\x8e`\x0e\xda\x10\x9b/\x18$\xf6\xa6M\n\xf9;\xcbu\xc2\xcc/\xce$i\xc9\n"\x8eY\xa7\xf7\x82\x0c\xd7\xd7k5\x9cC\x00j\xc4\x95g\xba\x9cE\xcb\xb8\x0e7\xf7\xdcN\x01O\xbe\n\xb6\x03\xd3\xad\x8aE\xf7\xda\'M)\xb1H\xdf\xe4\x11\xe4\x96F\xbdl\x02>\xd6Q\xc8\x95\x17\x01\x15\xa9\xf2\xaa\xaa\xf2\xbf/e\x1bo\xd0\xb9\x1a\x93\xf5\x8e5\xc4\x80\x87>\x94/f\xe4\xe9\xa8\xffA\x9cp*O*9\x18\x95\x1e~\xfba\x01<Q\x08.(\x18\xa4\x16\x0f1\xfd:l#\x93 v\xe1\xfd\x07\x85\xd1[?\xd2\x1cs2\xdd\xfa\xb9\xf8\x8c\xcf\x02\x87z\x9a\x96\xe4\xedO\x89\x8dSC\xab\x0e\x13\xc0\x01\x15\xb4y8\xdb\xfcn=\x9eQ\xb6\xb8\x13\x8bg\xcf\xf9|\xd9"\x1d\xf6]\xc5\x1c\x01/\x98\xe8z$\x18\xbc\x84\xd7\xfa\xdcr[\xf7\xc1:h'

The Context class must be specified:

>>> (dcert,remain) = BERcodec_Object.dec(cert, context=ASN1_Class_X509)

>>> dcert.show()

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_X509_CONT0:

<ASN1_INTEGER[2L]>

<ASN1_INTEGER[1L]>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.1.2.840.113549.1.1.5']>

<ASN1_NULL[0L]>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.6']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['US']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.10']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['AOL Time Warner Inc.']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.11']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['America Online Inc.']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.3']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['AOL Time Warner Root Certification Authority 2']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_UTC_TIME['020529060000Z']>

<ASN1_UTC_TIME['370928234300Z']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.6']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['US']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.10']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['AOL Time Warner Inc.']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.11']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['America Online Inc.']>

# ASN1_SET:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.4.3']>

<ASN1_PRINTABLE_STRING['AOL Time Warner Root Certification Authority 2']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.1.2.840.113549.1.1.1']>

<ASN1_NULL[0L]>

<ASN1_BIT_STRING['\x000\x82\x02\n\x02\x82\x02\x01\x00\xb47Z\x08\x16\x99\x14\xe8U\xb1\x1b$k\xfc\xc7\x8b\xe6\x87\xa9\x89\xee\x8b\x99\xcdO@\x86\xa4\xb6M\xc9\xd9\xb1\xdc<M\r\x85L\x15lF\x8bRx\x9f\xf8#\xfdg\xf5$:h]\xd0\xf7daAT\xa3\x8b\xa5\x08\xd2)[\x9b`O&\x83\xd1c\x12VIv\xa4\x16\xc2\xa5\x9dE\xac\x8b\x84\x95\xa8\x16\xb1\xec\x9f\xea$\x1a\xef\xb9W\\\x9a$!,M\x0eq\x1f\xa6\xac]Et\x03\x98\xc4T\x8c\x16JAw\x86\x95u\x0cG\x01f`\xfc\x15\xf1\x0f\xea\xf5\x14x\xc7\x0e\xd7n\x81\x1c^\xbf^\xe7:*\xd8\x97\x170|\x00\xad\x08\x9d3\xaf\xb8\x99a\x80\x8b\xa8\x95~\x14\xdc\x12l\xa4\xd0\xd8\xef@I\x026\xf9n\xa9\xd6\x1d\x96V\x04\xb2\xb3-\x16V\x86\x8f\xd9 W\x80\xcdg\x10m\xb0L\xf0\xdaF\xb6\xea%.F\xaf\x8d\xb0\x8584\x8b\x14&\x82+\xac\xae\x99\x0b\x8e\x14\xd7R\xbd\x9ei\xc3\x86\x02\x0b\xeavu1\t\xce3\x19!\x85C\xe6\x89-\x9f%7g\xf1#j\xd2\x00m\x97\xf9\x9f\xe7)\xca\xdd\x1f\xd7\x06\xea\xb8\xc9\xb9\t!\x9f\xc8?\x06\xc5\xd2\xe9\x12F\x00N{\x08\xebB=+Hn\x9dg\xddK\x02\xe4D\xf3\x93\x19\xa5\'\xceiz\xbeg\xd3\xfcP\xa4,\xab\xc3k\xb9\xe3\x80L\xcf\x05aK+\xdc\x1b\xb9\xa6\xd2\xd0\xaa\xf5+s\xfb\xce\x905\x9f\x0cR\x1c\xbf\\!a\x11[\x15K\xa9$Q\xfc\xa4\\\xf7\x17\x9d\xb0\xd2\xfa\x07\xe9\x8fV\xe4\x1a\x8ch\x8a\x04\xd3|Z\xe3\x9e\xa2\xa1\xcaq[\xa2\xd4\xa0\xe7)\x85]\x03h*O\xd2\x06\xd7=\xf9\xc3\x03/?e\xf9g\x1eG@\xd3c\x0f\xe3\xd5\x8e\xf9\x85\xab\x97L\xb3\xd7&\xeb\x96\n\x94\xde\x856\x9c\xc8\x7f\x81\t\x02I*\x0e\xf5d2\x0c\x82\xd1\xbaj\x82\x1b\xb3Kt\x11\xf3\x8cw\xd6\x9f\xbf\xdc7\xa4\xa7U\x04/\xd41\xe8\xd3F\xb9\x03|\xda\x12NYd\xb7Q11P\xa0\xca\x1c\'\xd9\x10.\xad\xd6\xbd\x10f+\xc3\xb0"J\x12[\x02\x03\x01\x00\x01']>

# ASN1_X509_CONT3:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.29.19']>

<ASN1_BOOLEAN[-1L]>

<ASN1_STRING['0\x03\x01\x01\xff']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.29.14']>

<ASN1_STRING['\x04\x14Oim\x03~\x9d\x9f\x07\x18C\xbc\xb7\x10N\xd5\xbf\xa9\xc4 (']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.29.35']>

<ASN1_STRING['0\x16\x80\x14Oim\x03~\x9d\x9f\x07\x18C\xbc\xb7\x10N\xd5\xbf\xa9\xc4 (']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.2.5.29.15']>

<ASN1_BOOLEAN[-1L]>

<ASN1_STRING['\x03\x02\x01\x86']>

# ASN1_SEQUENCE:

<ASN1_OID['.1.2.840.113549.1.1.5']>

<ASN1_NULL[0L]>

<ASN1_BIT_STRING['\x00;\xf3\xae\xca\xe8.\x87\x85\xfbeY\xe7\xad\x11\x14\xa5W\xbcX\x9f$\x12W\xbb\xfb?4\xda\xee\xadz*4rp1k\xc7\x19\x98\x80\xc9\x82\xde7w^T\x8b\x8e\xf2\xeagO\xc9t\x84\x91V\t\xd5\xe5z\x9a\x81\xb6\x81\xc2\xad6\xe4\xf1T\x11S\xf34E\x01&\xc8\xe5\x1a\xbc4D!\xde\xad%\xfcv\x16w!\x90\x80\x98W\x9dN\xea\xec/\xaa<\x14{W\xc1~\x18\x14g\xee$\xc6\xbd\xba\x15\xb0\xd2\x18\xbd\xb7U\x81\xacS\xc0\xe8\xddi\x12\x13B\xb7\x02\xb5\x05A\xcayPn\x82\x0eqr\x93F\xe8\x9d\r]\xbd\xae\xce)\xadc\xd5U\x16\x800\'\xffv\xba\xf7\xb8\xd6J\xe3\xd9\xb5\xf9R\xd0N@\xa9\xc7\xe5\xc22\xc7\xaav$\xe1k\x05P\xeb\xc5\xbf\nT\xe5\xb9B<$\xfb\xb7\x07\x9c0\x9fyZ\xe6\xe0@R\x15\xf4\xfc\xaa\xf4V\xf9D\x97\x87\xed\x0eer^\xbe&\xfbM\xa4-\x08\x07\xde\xd8\\\xa0\xdc\x813\x99\x18%\x11w\xa7\xeb\xfdX\t,\x99k\x1b\x8a\xf3R?\x1aMH`\xf1\xa0\xf63\x02S\x8b\xed%\t\xb8\r-\xed\x97s\xec\xd7\x96\x1f\x8e`\x0e\xda\x10\x9b/\x18$\xf6\xa6M\n\xf9;\xcbu\xc2\xcc/\xce$i\xc9\n"\x8eY\xa7\xf7\x82\x0c\xd7\xd7k5\x9cC\x00j\xc4\x95g\xba\x9cE\xcb\xb8\x0e7\xf7\xdcN\x01O\xbe\n\xb6\x03\xd3\xad\x8aE\xf7\xda\'M)\xb1H\xdf\xe4\x11\xe4\x96F\xbdl\x02>\xd6Q\xc8\x95\x17\x01\x15\xa9\xf2\xaa\xaa\xf2\xbf/e\x1bo\xd0\xb9\x1a\x93\xf5\x8e5\xc4\x80\x87>\x94/f\xe4\xe9\xa8\xffA\x9cp*O*9\x18\x95\x1e~\xfba\x01<Q\x08.(\x18\xa4\x16\x0f1\xfd:l#\x93 v\xe1\xfd\x07\x85\xd1[?\xd2\x1cs2\xdd\xfa\xb9\xf8\x8c\xcf\x02\x87z\x9a\x96\xe4\xedO\x89\x8dSC\xab\x0e\x13\xc0\x01\x15\xb4y8\xdb\xfcn=\x9eQ\xb6\xb8\x13\x8bg\xcf\xf9|\xd9"\x1d\xf6]\xc5\x1c\x01/\x98\xe8z$\x18\xbc\x84\xd7\xfa\xdcr[\xf7\xc1:h']>

ASN.1 layers

While this may be nice, it’s only an ASN.1 encoder/decoder. Nothing related to Scapy yet.

ASN.1 fields

Scapy provides ASN.1 fields. They will wrap ASN.1 objects and provide the necessary logic to bind a field name to the value. ASN.1 packets will be described as a tree of ASN.1 fields. Then each field name will be made available as a normal Packet object, in a flat flavor (ex: to access the version field of a SNMP packet, you don’t need to know how many containers wrap it).

Each ASN.1 field is linked to an ASN.1 object through its tag.

ASN.1 packets

ASN.1 packets inherit from the Packet class. Instead of a fields_desc list of fields, they define ASN1_codec and ASN1_root attributes. The first one is a codec (for example: ASN1_Codecs.BER), the second one is a tree compounded with ASN.1 fields.

A complete example: SNMP

SNMP defines new ASN.1 objects. We need to define them:

class ASN1_Class_SNMP(ASN1_Class_UNIVERSAL):

name="SNMP"

PDU_GET = 0xa0

PDU_NEXT = 0xa1

PDU_RESPONSE = 0xa2

PDU_SET = 0xa3

PDU_TRAPv1 = 0xa4

PDU_BULK = 0xa5

PDU_INFORM = 0xa6

PDU_TRAPv2 = 0xa7

These objects are PDU, and are in fact new names for a sequence container (this is generally the case for context objects: they are old containers with new names). This means creating the corresponding ASN.1 objects and BER codecs is simplistic:

class ASN1_SNMP_PDU_GET(ASN1_SEQUENCE):

tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_GET

class ASN1_SNMP_PDU_NEXT(ASN1_SEQUENCE):

tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_NEXT

# [...]

class BERcodec_SNMP_PDU_GET(BERcodec_SEQUENCE):

tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_GET

class BERcodec_SNMP_PDU_NEXT(BERcodec_SEQUENCE):

tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_NEXT

# [...]

Metaclasses provide the magic behind the fact that everything is automatically registered and that ASN.1 objects and BER codecs can find each other.

The ASN.1 fields are also trivial:

class ASN1F_SNMP_PDU_GET(ASN1F_SEQUENCE):

ASN1_tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_GET

class ASN1F_SNMP_PDU_NEXT(ASN1F_SEQUENCE):

ASN1_tag = ASN1_Class_SNMP.PDU_NEXT

# [...]

Now, the hard part, the ASN.1 packet:

SNMP_error = { 0: "no_error",

1: "too_big",

# [...]

}

SNMP_trap_types = { 0: "cold_start",

1: "warm_start",

# [...]

}

class SNMPvarbind(ASN1_Packet):

ASN1_codec = ASN1_Codecs.BER

ASN1_root = ASN1F_SEQUENCE( ASN1F_OID("oid","1.3"),

ASN1F_field("value",ASN1_NULL(0))

)

class SNMPget(ASN1_Packet):

ASN1_codec = ASN1_Codecs.BER

ASN1_root = ASN1F_SNMP_PDU_GET( ASN1F_INTEGER("id",0),

ASN1F_enum_INTEGER("error",0, SNMP_error),

ASN1F_INTEGER("error_index",0),

ASN1F_SEQUENCE_OF("varbindlist", [], SNMPvarbind)

)

class SNMPnext(ASN1_Packet):

ASN1_codec = ASN1_Codecs.BER

ASN1_root = ASN1F_SNMP_PDU_NEXT( ASN1F_INTEGER("id",0),

ASN1F_enum_INTEGER("error",0, SNMP_error),

ASN1F_INTEGER("error_index",0),

ASN1F_SEQUENCE_OF("varbindlist", [], SNMPvarbind)

)

# [...]

class SNMP(ASN1_Packet):

ASN1_codec = ASN1_Codecs.BER

ASN1_root = ASN1F_SEQUENCE(

ASN1F_enum_INTEGER("version", 1, {0:"v1", 1:"v2c", 2:"v2", 3:"v3"}),

ASN1F_STRING("community","public"),

ASN1F_CHOICE("PDU", SNMPget(),

SNMPget, SNMPnext, SNMPresponse, SNMPset,

SNMPtrapv1, SNMPbulk, SNMPinform, SNMPtrapv2)

)

def answers(self, other):

return ( isinstance(self.PDU, SNMPresponse) and

( isinstance(other.PDU, SNMPget) or

isinstance(other.PDU, SNMPnext) or

isinstance(other.PDU, SNMPset) ) and

self.PDU.id == other.PDU.id )

# [...]

bind_layers( UDP, SNMP, sport=161)

bind_layers( UDP, SNMP, dport=161)

That wasn’t that much difficult. If you think that can’t be that short to implement SNMP encoding/decoding and that I may have cut too much, just look at the complete source code.

Now, how to use it? As usual:

>>> a=SNMP(version=3, PDU=SNMPget(varbindlist=[SNMPvarbind(oid="1.2.3",value=5),

... SNMPvarbind(oid="3.2.1",value="hello")]))

>>> a.show()

###[ SNMP ]###

version= v3

community= 'public'

\PDU\

|###[ SNMPget ]###

| id= 0

| error= no_error

| error_index= 0

| \varbindlist\

| |###[ SNMPvarbind ]###

| | oid= '1.2.3'

| | value= 5

| |###[ SNMPvarbind ]###

| | oid= '3.2.1'

| | value= 'hello'

>>> hexdump(a)

0000 30 2E 02 01 03 04 06 70 75 62 6C 69 63 A0 21 02 0......public.!.

0010 01 00 02 01 00 02 01 00 30 16 30 07 06 02 2A 03 ........0.0...*.

0020 02 01 05 30 0B 06 02 7A 01 04 05 68 65 6C 6C 6F ...0...z...hello

>>> send(IP(dst="1.2.3.4")/UDP()/SNMP())

.

Sent 1 packets.

>>> SNMP(raw(a)).show()

###[ SNMP ]###

version= <ASN1_INTEGER[3L]>

community= <ASN1_STRING['public']>

\PDU\

|###[ SNMPget ]###

| id= <ASN1_INTEGER[0L]>

| error= <ASN1_INTEGER[0L]>

| error_index= <ASN1_INTEGER[0L]>

| \varbindlist\

| |###[ SNMPvarbind ]###

| | oid= <ASN1_OID['.1.2.3']>

| | value= <ASN1_INTEGER[5L]>

| |###[ SNMPvarbind ]###

| | oid= <ASN1_OID['.3.2.1']>

| | value= <ASN1_STRING['hello']>

Resolving OID from a MIB

About OID objects

OID objects are created with an ASN1_OID class:

>>> o1=ASN1_OID("2.5.29.10")

>>> o2=ASN1_OID("1.2.840.113549.1.1.1")

>>> o1,o2

(<ASN1_OID['.2.5.29.10']>, <ASN1_OID['.1.2.840.113549.1.1.1']>)

Loading a MIB

Scapy can parse MIB files and become aware of a mapping between an OID and its name:

>>> load_mib("mib/*")

>>> o1,o2

(<ASN1_OID['basicConstraints']>, <ASN1_OID['rsaEncryption']>)

The MIB files I’ve used are attached to this page.

Scapy’s MIB database

All MIB information is stored into the conf.mib object. This object can be used to find the OID of a name

>>> conf.mib.sha1_with_rsa_signature

'1.2.840.113549.1.1.5'

or to resolve an OID:

>>> conf.mib._oidname("1.2.3.6.1.4.1.5")

'enterprises.5'

It is even possible to graph it:

>>> conf.mib._make_graph()

Automata

Scapy enables to create easily network automata. Scapy does not stick to a specific model like Moore or Mealy automata. It provides a flexible way for you to choose your way to go.

An automaton in Scapy is deterministic. It has different states. A start state and some end and error states. There are transitions from one state to another. Transitions can be transitions on a specific condition, transitions on the reception of a specific packet or transitions on a timeout. When a transition is taken, one or more actions can be run. An action can be bound to many transitions. Parameters can be passed from states to transitions, and from transitions to states and actions.

From a programmer’s point of view, states, transitions and actions are methods from an Automaton subclass. They are decorated to provide meta-information needed in order for the automaton to work.

First example

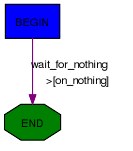

Let’s begin with a simple example. I take the convention to write states with capitals, but anything valid with Python syntax would work as well.

class HelloWorld(Automaton):

@ATMT.state(initial=1)

def BEGIN(self):

print("State=BEGIN")

@ATMT.condition(BEGIN)

def wait_for_nothing(self):

print("Wait for nothing...")

raise self.END()

@ATMT.action(wait_for_nothing)

def on_nothing(self):

print("Action on 'nothing' condition")

@ATMT.state(final=1)

def END(self):

print("State=END")

In this example, we can see 3 decorators:

ATMT.statethat is used to indicate that a method is a state, and that can have initial, final, stop and error optional arguments set to non-zero for special states.ATMT.conditionthat indicate a method to be run when the automaton state reaches the indicated state. The argument is the name of the method representing that stateATMT.actionbinds a method to a transition and is run when the transition is taken.

Running this example gives the following result:

>>> a=HelloWorld()

>>> a.run()

State=BEGIN

Wait for nothing...

Action on 'nothing' condition

State=END

>>> a.destroy()

This simple automaton can be described with the following graph:

The graph can be automatically drawn from the code with:

>>> HelloWorld.graph()

Note

An Automaton can be reset using restart(). It is then possible to run it again.

Warning

Remember to call destroy() once you’re done using an Automaton. (especially on PyPy)

Changing states

The ATMT.state decorator transforms a method into a function that returns an exception. If you raise that exception, the automaton state will be changed. If the change occurs in a transition, actions bound to this transition will be called. The parameters given to the function replacing the method will be kept and finally delivered to the method. The exception has a method action_parameters that can be called before it is raised so that it will store parameters to be delivered to all actions bound to the current transition.

As an example, let’s consider the following state:

@ATMT.state()

def MY_STATE(self, param1, param2):

print("state=MY_STATE. param1=%r param2=%r" % (param1, param2))

This state will be reached with the following code:

@ATMT.receive_condition(ANOTHER_STATE)

def received_ICMP(self, pkt):

if ICMP in pkt:

raise self.MY_STATE("got icmp", pkt[ICMP].type)

Let’s suppose we want to bind an action to this transition, that will also need some parameters:

@ATMT.action(received_ICMP)

def on_ICMP(self, icmp_type, icmp_code):

self.retaliate(icmp_type, icmp_code)

The condition should become:

@ATMT.receive_condition(ANOTHER_STATE)

def received_ICMP(self, pkt):

if ICMP in pkt:

raise self.MY_STATE("got icmp", pkt[ICMP].type).action_parameters(pkt[ICMP].type, pkt[ICMP].code)

Real example

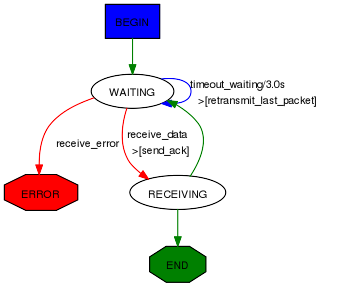

Here is a real example take from Scapy. It implements a TFTP client that can issue read requests.

class TFTP_read(Automaton):

def parse_args(self, filename, server, sport = None, port=69, **kargs):

Automaton.parse_args(self, **kargs)

self.filename = filename

self.server = server

self.port = port

self.sport = sport

def master_filter(self, pkt):

return ( IP in pkt and pkt[IP].src == self.server and UDP in pkt

and pkt[UDP].dport == self.my_tid

and (self.server_tid is None or pkt[UDP].sport == self.server_tid) )

# BEGIN

@ATMT.state(initial=1)

def BEGIN(self):

self.blocksize=512

self.my_tid = self.sport or RandShort()._fix()

bind_bottom_up(UDP, TFTP, dport=self.my_tid)

self.server_tid = None

self.res = b""

self.l3 = IP(dst=self.server)/UDP(sport=self.my_tid, dport=self.port)/TFTP()

self.last_packet = self.l3/TFTP_RRQ(filename=self.filename, mode="octet")

self.send(self.last_packet)

self.awaiting=1

raise self.WAITING()

# WAITING

@ATMT.state()

def WAITING(self):

pass

@ATMT.receive_condition(WAITING)

def receive_data(self, pkt):

if TFTP_DATA in pkt and pkt[TFTP_DATA].block == self.awaiting:

if self.server_tid is None:

self.server_tid = pkt[UDP].sport

self.l3[UDP].dport = self.server_tid

raise self.RECEIVING(pkt)

@ATMT.action(receive_data)

def send_ack(self):

self.last_packet = self.l3 / TFTP_ACK(block = self.awaiting)

self.send(self.last_packet)

@ATMT.receive_condition(WAITING, prio=1)

def receive_error(self, pkt):

if TFTP_ERROR in pkt:

raise self.ERROR(pkt)

@ATMT.timeout(WAITING, 3)

def timeout_waiting(self):

raise self.WAITING()

@ATMT.action(timeout_waiting)

def retransmit_last_packet(self):

self.send(self.last_packet)

# RECEIVED

@ATMT.state()

def RECEIVING(self, pkt):

recvd = pkt[Raw].load

self.res += recvd

self.awaiting += 1

if len(recvd) == self.blocksize:

raise self.WAITING()

raise self.END()

# ERROR

@ATMT.state(error=1)

def ERROR(self,pkt):

split_bottom_up(UDP, TFTP, dport=self.my_tid)

return pkt[TFTP_ERROR].summary()

#END

@ATMT.state(final=1)

def END(self):

split_bottom_up(UDP, TFTP, dport=self.my_tid)

return self.res

It can be run like this, for instance:

>>> atmt = TFTP_read("my_file", "192.168.1.128")

>>> atmt.run()

>>> atmt.destroy()

Detailed documentation

Decorators

Decorator for states

States are methods decorated by the result of the ATMT.state function. It can take 4 optional parameters, initial, final, stop and error, that, when set to True, indicating that the state is an initial, final, stop or error state.

Note

The initial state is called while starting the automata. The final step will tell the automata has reached its end. If you call atmt.stop(), the automata will move to the stop step whatever its current state is. The error state will mark the automata as errored. If no stop state is specified, calling stop and forcestop will be equivalent.

class Example(Automaton):

@ATMT.state(initial=1)

def BEGIN(self):

pass

@ATMT.state()

def SOME_STATE(self):

pass

@ATMT.state(final=1)

def END(self):

return "Result of the automaton: 42"

@ATMT.state(stop=1)

def STOP(self):

print("SHUTTING DOWN...")

# e.g. close sockets...

@ATMT.condition(STOP)

def is_stopping(self):

raise self.END()

@ATMT.state(error=1)

def ERROR(self):

return "Partial result, or explanation"

# [...]

Take for instance the TCP client:

The START event is initial=1, the STOP event is stop=1 and the CLOSED event is final=1.

Decorators for transitions

Transitions are methods decorated by the result of one of ATMT.condition, ATMT.receive_condition, ATMT.eof, ATMT.timeout, ATMT.timer. They all take as argument the state method they are related to. ATMT.timeout and ATMT.timer also have a mandatory timeout parameter to provide the timeout value in seconds. The difference between ATMT.timeout and ATMT.timer is that ATMT.timeout gets triggered only once. ATMT.timer get reloaded automatically, which is useful for sending keep-alive packets. ATMT.condition and ATMT.receive_condition have an optional prio parameter so that the order in which conditions are evaluated can be forced. The default priority is 0. Transitions with the same priority level are called in an undetermined order.

When the automaton switches to a given state, the state’s method is executed. Then transitions methods are called at specific moments until one triggers a new state (something like raise self.MY_NEW_STATE()). First, right after the state’s method returns, the ATMT.condition decorated methods are run by growing prio. Then each time a packet is received and accepted by the master filter all ATMT.receive_condition decorated hods are called by growing prio. When a timeout is reached since the time we entered into the current space, the corresponding ATMT.timeout decorated method is called. If the socket raises an EOFError (closed) during a state, the ATMT.EOF transition is called. Otherwise it raises an exception and the automaton exits.

class Example(Automaton):

@ATMT.state()

def WAITING(self):

pass

@ATMT.condition(WAITING)

def it_is_raining(self):

if not self.have_umbrella:

raise self.ERROR_WET()

@ATMT.receive_condition(WAITING, prio=1)

def it_is_ICMP(self, pkt):

if ICMP in pkt:

raise self.RECEIVED_ICMP(pkt)

@ATMT.receive_condition(WAITING, prio=2)

def it_is_IP(self, pkt):

if IP in pkt:

raise self.RECEIVED_IP(pkt)

@ATMT.timeout(WAITING, 10.0)

def waiting_timeout(self):

raise self.ERROR_TIMEOUT()

Decorator for actions

Actions are methods that are decorated by the return of ATMT.action function. This function takes the transition method it is bound to as first parameter and an optional priority prio as a second parameter. The default priority is 0. An action method can be decorated many times to be bound to many transitions.

from random import random

class Example(Automaton):

@ATMT.state(initial=1)

def BEGIN(self):

pass

@ATMT.state(final=1)

def END(self):

pass

@ATMT.condition(BEGIN, prio=1)

def maybe_go_to_end(self):

if random() > 0.5:

raise self.END()

@ATMT.condition(BEGIN, prio=2)

def certainly_go_to_end(self):

raise self.END()

@ATMT.action(maybe_go_to_end)

def maybe_action(self):

print("We are lucky...")

@ATMT.action(certainly_go_to_end)

def certainly_action(self):

print("We are not lucky...")

@ATMT.action(maybe_go_to_end, prio=1)

@ATMT.action(certainly_go_to_end, prio=1)

def always_action(self):

print("This wasn't luck!...")

The two possible outputs are:

>>> a=Example()

>>> a.run()

We are not lucky...

This wasn't luck!...

>>> a.run()

We are lucky...

This wasn't luck!...

>>> a.destroy()

Note

If you want to pass a parameter to an action, you can use the action_parameters function while raising the next state.

In the following example, the send_copy action takes a parameter passed by is_fin:

class Example(Automaton):

@ATMT.state()

def WAITING(self):

pass

@ATMT.state()

def FIN_RECEIVED(self):

pass

@ATMT.receive_condition(WAITING)

def is_fin(self, pkt):

if pkt[TCP].flags.F:

raise self.FIN_RECEIVED().action_parameters(pkt)

@ATMT.action(is_fin)

def send_copy(self, pkt):

send(pkt)

Methods to overload

Two methods are hooks to be overloaded:

The

parse_args()method is called with arguments given at__init__()andrun(). Use that to parametrize the behavior of your automaton.The

master_filter()method is called each time a packet is sniffed and decides if it is interesting for the automaton. When working on a specific protocol, this is where you will ensure the packet belongs to the connection you are being part of, so that you do not need to make all the sanity checks in each transition.

Timer configuration

Some protocols allow timer configuration. In order to configure timeout values during class initialization one may use timer_by_name() method, which returns Timer object associated with the given function name:

class Example(Automaton):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super(Example, self).__init__(*args, **kwargs)

timer = self.timer_by_name("waiting_timeout")

timer.set(1)

@ATMT.state(initial=1)

def WAITING(self):

pass

@ATMT.state(final=1)

def END(self):

pass

@ATMT.timeout(WAITING, 10.0)

def waiting_timeout(self):

raise self.END()

PipeTools

Scapy’s pipetool is a smart piping system allowing to perform complex stream data management.

The goal is to create a sequence of steps with one or several inputs and one or several outputs, with a bunch of blocks in between. PipeTools can handle varied sources of data (and outputs) such as user input, pcap input, sniffing, wireshark… A pipe system is implemented by manually linking all its parts. It is possible to dynamically add an element while running or set multiple drains for the same source.

Note

Pipetool default objects are located inside scapy.pipetool

Demo: sniff, anonymize, send to Wireshark

The following code will sniff packets on the default interface, anonymize the source and destination IP addresses and pipe it all into Wireshark. Useful when posting online examples, for instance.

source = SniffSource(iface=conf.iface)

wire = WiresharkSink()

def transf(pkt):

if not pkt or IP not in pkt:

return pkt

pkt[IP].src = "1.1.1.1"

pkt[IP].dst = "2.2.2.2"

return pkt

source > TransformDrain(transf) > wire

p = PipeEngine(source)

p.start()

p.wait_and_stop()

The engine is pretty straightforward:

Let’s run it:

Class Types

There are 3 different class of objects used for data management:

SourcesDrainsSinks

They are executed and handled by a PipeEngine object.

When running, a pipetool engine waits for any available data from the Source, and send it in the Drains linked to it. The data then goes from Drains to Drains until it arrives in a Sink, the final state of this data.

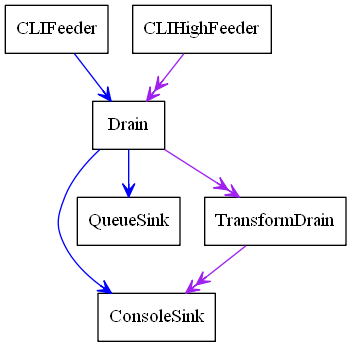

Let’s see with a basic demo how to build a pipetool system.

For instance, this engine was generated with this code:

>>> s = CLIFeeder()

>>> s2 = CLIHighFeeder()

>>> d1 = Drain()

>>> d2 = TransformDrain(lambda x: x[::-1])

>>> si1 = ConsoleSink()

>>> si2 = QueueSink()

>>>

>>> s > d1

>>> d1 > si1

>>> d1 > si2

>>>

>>> s2 >> d1

>>> d1 >> d2

>>> d2 >> si1

>>>

>>> p = PipeEngine()

>>> p.add(s)

>>> p.add(s2)

>>> p.graph(target="> the_above_image.png")

start() is used to start the PipeEngine:

>>> p.start()

Now, let’s play with it by sending some input data

>>> s.send("foo")

>'foo'

>>> s2.send("bar")

>>'rab'

>>> s.send("i like potato")

>'i like potato'

>>> print(si2.recv(), ":", si2.recv())

foo : i like potato

Let’s study what happens here:

there are two canals in a

PipeEngine, a lower one and a higher one. Some Sources write on the lower one, some on the higher one and some on both.most sources can be linked to any drain, on both lower and higher canals. The use of

>indicates a link on the low canal, and>>on the higher one.when we send some data in

s, which is on the lower canal, as shown above, it goes through theDrainthen is sent to theQueueSinkand to theConsoleSinkwhen we send some data in

s2, it goes through the Drain, then the TransformDrain where the data is reversed (see the lambda), before being sent toConsoleSinkonly. This explains why we only have the data of the lower sources inside the QueueSink: the higher one has not been linked.

Most of the sinks receive from both lower and upper canals. This is verifiable using the help(ConsoleSink)

>>> help(ConsoleSink)

Help on class ConsoleSink in module scapy.pipetool:

class ConsoleSink(Sink)

| Print messages on low and high entries

| +-------+

| >>-|--. |->>

| | print |

| >-|--' |->

| +-------+

|

[...]

Sources

A Source is a class that generates some data.

There are several source types integrated with Scapy, usable as-is, but you may also create yours.

Default Source classes

For any of those class, have a look at help([theclass]) to get more information or the required parameters.

CLIFeeder: a source especially used in interactive software. itssend(data)generates the event data on the lower canalCLIHighFeeder: same than CLIFeeder, but writes on the higher canalPeriodicSource: Generate messages periodically on the low canal.AutoSource: the default source, that must be extended to create custom sources.

Create a custom Source

To create a custom source, one must extend the AutoSource class.

Note

Do NOT use the default Source class except if you are really sure of what you are doing: it is only used internally, and is missing some implementation. The AutoSource is made to be used.

To send data through it, the object must call its self._gen_data(msg) or self._gen_high_data(msg) functions, which send the data into the PipeEngine.

The Source should also (if possible), set self.is_exhausted to True when empty, to allow the clean stop of the PipeEngine. If the source is infinite, it will need a force-stop (see PipeEngine below)

For instance, here is how CLIHighFeeder is implemented:

class CLIFeeder(CLIFeeder):

def send(self, msg):

self._gen_high_data(msg)

def close(self):

self.is_exhausted = True

Drains

Default Drain classes

Drains need to be linked on the entry that you are using. It can be either on the lower one (using >) or the upper one (using >>).

See the basic example above.

Drain: the most basic Drain possible. Will pass on both low and high entry if linked properly.TransformDrain: Apply a function to messages on low and high entryUpDrain: Repeat messages from low entry to high exitDownDrain: Repeat messages from high entry to low exit

Create a custom Drain

To create a custom drain, one must extend the Drain class.

A Drain object will receive data from the lower canal in its push method, and from the higher canal from its high_push method.

To send the data back into the next linked Drain / Sink, it must call the self._send(msg) or self._high_send(msg) methods.

For instance, here is how TransformDrain is implemented:

class TransformDrain(Drain):

def __init__(self, f, name=None):

Drain.__init__(self, name=name)

self.f = f

def push(self, msg):

self._send(self.f(msg))

def high_push(self, msg):

self._high_send(self.f(msg))

Sinks

Sinks are destinations for messages.

A Sink receives data like a Drain, but doesn’t send any

messages after it.

Messages on the low entry come from push(), and messages on the

high entry come from high_push().

Default Sinks classes

ConsoleSink: Print messages on low and high entries tostdoutRawConsoleSink: Print messages on low and high entries, using os.writeTermSink: Prints messages on the low and high entries, on a separate terminalQueueSink: Collects messages on the low and high entries into aQueue

Create a custom Sink

To create a custom sink, one must extend Sink and implement

push() and/or high_push().

This is a simplified version of ConsoleSink:

class ConsoleSink(Sink):

def push(self, msg):

print(">%r" % msg)

def high_push(self, msg):

print(">>%r" % msg)

Link objects

As shown in the example, most sources can be linked to any drain, on both low and high entry.

The use of > indicates a link on the low entry, and >> on the high

entry.

For example, to link a, b and c on the low entries:

>>> a = CLIFeeder()

>>> b = Drain()

>>> c = ConsoleSink()

>>> a > b > c

>>> p = PipeEngine()

>>> p.add(a)

This wouldn’t link the high entries, so something like this would do nothing:

>>> a2 = CLIHighFeeder()

>>> a2 >> b

>>> a2.send("hello")

Because b (Drain) and c (scapy.pipetool.ConsoleSink) are not

linked on the high entry.

However, using a DownDrain would bring the high messages from

CLIHighFeeder to the lower channel:

>>> a2 = CLIHighFeeder()

>>> b2 = DownDrain()

>>> a2 >> b2

>>> b2 > b

>>> a2.send("hello")

The PipeEngine class

The PipeEngine class is the core class of the Pipetool system. It must be initialized and passed the list of all Sources.

There are two ways of passing sources:

during initialization:

p = PipeEngine(source1, source2, ...)using the

add(source)method

A PipeEngine class must be started with .start() function. It may be force-stopped with the .stop(), or cleanly stopped with .wait_and_stop()

A clean stop only works if the Sources is exhausted (has no data to send left).

It can be printed into a graph using .graph() methods. see help(do_graph) for the list of available keyword arguments.

Scapy advanced PipeTool objects

Note

Unlike the previous objects, those are not located in scapy.pipetool but in scapy.scapypipes

Now that you know the default PipeTool objects, here are some more advanced ones, based on packet functionalities.

SniffSource: Read packets from an interface and send them to low exit.RdpcapSource: Read packets from a PCAP file send them to low exit.InjectSink: Packets received on low input are injected (sent) to an interfaceWrpcapSink: Packets received on low input are written to PCAP fileUDPDrain: UDP payloads received on high entry are sent over UDP (complicated, have a look athelp(UDPDrain))FDSourceSink: Use a file descriptor as source and sinkTCPConnectPipe: TCP connect to addr:port and use it as source and sinkTCPListenPipe: TCP listen on [addr:]port and use the first connection as source and sink (complicated, have a look athelp(TCPListenPipe))

Triggering

Some special sort of Drains exists: the Trigger Drains.

Trigger Drains are special drains, that on receiving data not only pass it by but also send a “Trigger” input, that is received and handled by the next triggered drain (if it exists).

For example, here is a basic TriggerDrain usage:

>>> a = CLIFeeder()

>>> d = TriggerDrain(lambda msg: True) # Pass messages and trigger when a condition is met

>>> d2 = TriggeredValve()

>>> s = ConsoleSink()

>>> a > d > d2 > s

>>> d ^ d2 # Link the triggers

>>> p = PipeEngine(s)

>>> p.start()

INFO: Pipe engine thread started.

>>>

>>> a.send("this will be printed")

>'this will be printed'

>>> a.send("this won't, because the valve was switched")

>>> a.send("this will, because the valve was switched again")

>'this will, because the valve was switched again'

>>> p.stop()

Several triggering Drains exist, they are pretty explicit. It is highly recommended to check the doc using help([the class])

TriggeredMessage: Send a preloaded message when triggered and trigger in chainTriggerDrain: Pass messages and trigger when a condition is metTriggeredValve: Let messages alternatively pass or not, changing on triggerTriggeredQueueingValve: Let messages alternatively pass or queued, changing on triggerTriggeredSwitch: Let messages alternatively high or low, changing on trigger